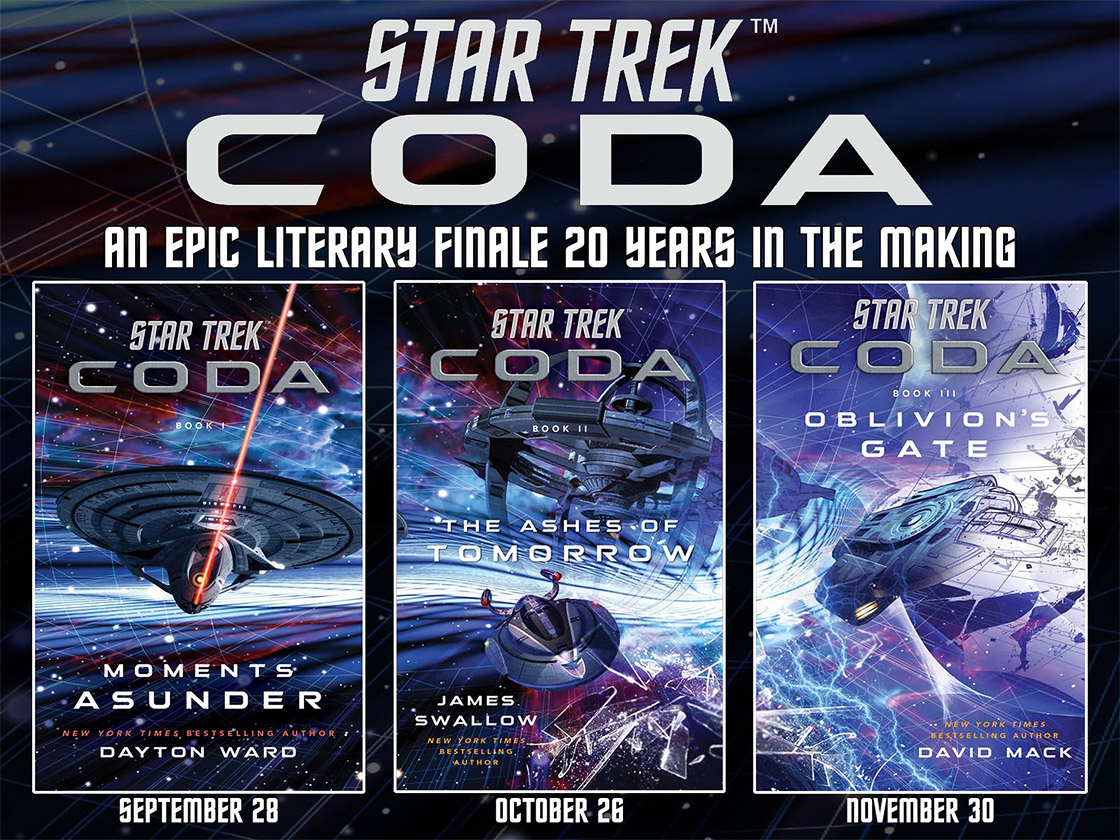

The world-ending Star Trek: Coda trilogy draws to a close this week with the publication David Mack’s Oblivion’s Gate, which concludes 20 years of literary continuity across most of the Star Trek novels published since the early 2000s — and it is a huge story.

My review of this third and final entry to the Coda saga will be out soon, where you’ll find my thoughts on how it served the wrap-up-the-Trek-litverse goal it promised, but in the meantime read on below as I dive into Oblivion’s Gate with author David Mack!

You can also find plenty of additional Star Trek: Coda coverage here at TrekCore, including my review of Dayton Ward’s Moments Asunder and James Swallow’s The Ashes of Tomorrow.

Finally, if you enjoy this conversation with David Mack, be sure to read my previous interviews with the Coda writing team, as authors Dayton Ward and James Swallow help to share the full behind-the-scenes picture on this massive literary project.

There are some MAJOR SPOILERS ahead for the ENTIRE Star Trek: Coda trilogy in the interview ahead — including how the massive tale ends! — so if you haven’t read all three books yet, come back after you’ve caught up!

TREKCORE: I’ve talked to Dayton and James about this — what’s your perspective on joining this team, and why did you want to write this conclusion for the Trek literary storyline?

TREKCORE: I’ve talked to Dayton and James about this — what’s your perspective on joining this team, and why did you want to write this conclusion for the Trek literary storyline?

DAVID MACK: We all tell pretty much the same story, naturally. In early 2018, the Star Trek television team at Secret Hideout began developing the series that became Star Trek: Picard. I was apprised of this by my friend Kirsten Beyer, one of the co-creators of Picard.

Around the same time, my friend Dayton Ward, who had at that time just begun working for the Star Trek licensing team at ViacomCBS, was seeing memos and outlines, etc., about the new show. As he noted details about its setting in the Star Trek chronology — 2399, at the end of the 24th century — he experienced the same realization that I was having at the same time: Treklit was about to have a canon continuity problem.

Specifically, because most of the stories in the post-finale, serialized continuity of the Star Trek novels published since 2003 (and some that went back as far as 2001) were set after the events of Star Trek: Nemesis — which was set in 2379 — many major events that had transpired as part of the novels’ shared continuity were very likely to be rendered apocryphal by new canon details in the back story of Picard.

Because tie-in fiction for Star Trek is expected to be consistent with the canon films and episodes as they exist at the time the tie-in work is written, I knew (as Dayton did) that once Picard debuted, the 20-year-long literary continuity was going to be rendered incompatible with canon.

We also knew that our publisher was likely to choose one of only two likely approaches to this situation: either it would simply cease producing the Star Trek books with serialized continuity and abandon their ongoing narratives, or, it would choose to do some sort of finale to bring the long narrative journey to a close. But in order for the publisher to choose the latter option, someone would have to pitch the editors an idea worth publishing.

Knowing that, both Dayton and I independently began imagining what might constitute such an “event,” and how we might go about getting it done.

A decade ago, I might have pitched a trilogy idea such as this on my own, and tried to write it solo. In recent years, however, the Star Trek books publishing schedule has contracted to fewer than 10 titles per year, so at this point the idea of handing an event trilogy to one writer might stir up a lot of bad blood among the other Trek authors.

Also, Dayton and I both knew that to get a project like this done in less than three years from pitch to publication would mean splitting up the work. It would take multiple authors, all working nearly simultaneously, to enable such an event project to be released without delays over a number of consecutive months.

It likely won’t surprise many folks to know that when Dayton and I considered who should work on a project such as this, he and I both listed each other on our rosters.

We also both were thinking that, in addition to the core trilogy, there might be a few other “breadcrumb” books that would be published ahead of it, to tie off some long-running story lines and to subtly set the stage for the trilogy; of course, the “breadcrumb” books ended up being kiboshed by the publisher — there was just no room for them in Star Trek’s already crowded publishing schedule.

But before we knew that, I had made up my mind with regard to my preferred collaborators. For me the “Dream Team” was always going to be me, Dayton, and James. We had worked well together in the past on Star Trek Vanguard, the Star Trek: The Fall miniseries, and the Tor/Forge tie-in novels for 24. Taking on this project with them felt to me like “getting the band back together.”

In July of 2019, James was in NYC for a convention of the International Thriller Writers. His visit coincided with the July 4th weekend, so I invited him to come with me and my wife to a friend’s barbecue in New Jersey. At the barbecue, I pitched James my idea for an epic trilogy to end the 20-year Star Trek literary continuity, told him why I thought it should be done, and asked him to come aboard.

“Absolutely not,” he replied. His refusal took me by surprise; I had thought he would jump at the idea. But he didn’t like it. He recoiled from the idea of a story that would, at least superficially, seem to undo decades of work done not just by us but by dozens of our friends and peers.

I needed to sell him on it. I made the case that there would be no stopping the juggernaut of Star Trek: Picard, and that once it arrived, some kind of decision would need to be made concerning the fate of the interconnected literary continuity. And here is where I turned him around: “Who would you rather made these decisions, James? Someone in Alex Kurtzman’s office, or us? And if the editors choose to publish an epic swansong for the last two decades of work that we and our friends have done, who would you rather see writing it than you?”

At that point, James was swayed. We spent the rest of the afternoon talking about the story with fellow Star Trek authors Keith R. A. DeCandido and Glenn Hauman, over brisket and beers. A couple of weeks later I went to the Shore Leave Convention in Hunt Valley, MD, to pitch my and James’s story to Dayton, in the hope that he would come aboard.

That was when I learned Dayton had been noodling on his own version of an almost identical story idea for the same length of time that I had — but he had far more detailed inside information than I did, so when he told me some part of my idea wouldn’t be workable because of canon events that would be revealed in Picard, I tried to adjust my pitch to compensate.

That’s when he stopped me and shook his head: “Dude. It’s so much worse than you think.” He was right, of course, but we forged ahead. Because his idea was so similar to the one James and I had concocted, we decided to join forces and develop the core story as a team. This was the beginning of what Dayton later came to refer to as “the Plan.”

TREKCORE: Oblivion’s Gate doesn’t just end Coda, but it feels like an end to many of the major stories you had a hand in over the last two decades as well — like Kira’s role as “Hand of the Prophets,” the Mirror Universe characters, and so forth.

What was it like revisiting so much of your own previous work, and trying to tie up all of those elements?

MACK: At times, the experience of revisiting so much of my past work in a single volume felt eerily nostalgic. In some cases, I took the opportunity to comment obliquely on my past works, or on critics’ receptions of them; in others, I focused on making sure that I took full advantage of the opportunities for closure that a project such as this affords.

The funny thing is, before James and I teamed up with Dayton, my original version of the pitch did not include the Borg, and it had made no use of Kira’s past anointment as “the Hand of the Prophets.” I had envisioned the time-travel aspects of this story to be more like what was done in Avengers: Endgame — a light-hearted, poignant, and ultimately consequential tour through Treklit’s greatest hits, as it were.

Once Dayton made his case for the Borg being at ground zero of the temporal disruption event, which set the point of divergence for The First Splinter timeline at 2373, I knew that the finale plot would have to entail a journey back into that nightmare vision of Earth — and, for Picard, one last confrontation with the enemy he thought he had seen the end of in 2381.

The inclusion of Kira’s status as “Hand of the Prophets” came about during development, when it became clear how pivotal she and Sisko were going to be in The Ashes of Tomorrow. I gave Kira that moniker in my 2006 Deep Space Nine novel Warpath, and it was meant to be part of editor Marco Palmieri’s long-term Ascendants story arc. I think David R. George III made use of it in that capacity, but when we saw the possibility of using it in a different context for Coda, we couldn’t resist the opportunity.

As for the Mirror Universe elements, of course, I knew I wanted to take those characters for one last spin before closing the book on this continuity. Likewise, Dayton, James, and I tried to include nods to as many different elements of the shared literary universe as we were able to do, within the constraints of the story — like the brief appearance of the S.C.E. crew from the Starship da Vinci, and similar cameos and guest sequences across all three books.

TREKCORE: Oblivion’s Gate explains that the literary continuity began from the “all Borg” alternate timeline seen in Star Trek: First Contact, the glimpse of an assimilated Earth that drove the Enterprise-E crew to go back in time.

How did you settle on that moment, which the book calls “The First Splinter,” as the divergence from on-screen storytelling?

MACK: You can blame the inclusion of the Borg entirely on Dayton Ward! When Dayton was considering how far back he would need to rewind the continuity to address all of the many changes Star Trek: Picard was likely to inflict upon the continuity, he knew that doing the bare minimum likely would not be good enough.

He couldn’t simply find some way to rewind to 2385, the year of the synths’ attack on Mars in Picard. By that late point, there were too many major discontinuities between the history of Picard and that of the post-Nemesis novels. Just rolling back to Nemesis didn’t explain the discontinuities of the A Time to… novel miniseries, which was a prequel to Star Trek Nemesis.

So, not only did we need to go back farther in time, we also needed to find a plausible trigger for a temporal divergence event. Fortunately, Dayton had already found it: the Enterprise-E’s jaunt back through time in Star Trek: First Contact.

Set in 2373 — well behind any point the Picard producers were likely to muck about with — First Contact was an ideal candidate for a temporal event that could spawn our new unstable timeline. (We had to do some temporal tap-dancing and technobabble soft-shoe to explain how the Borg Earth of 2373 could still be visited after the events of the movie, but I think we pulled it off.)

Of course, once we agreed on that as the “original divergence event, or ODE,” it became obvious that we were going to need to make major use of it in the trilogy’s conclusion, as a key step to “doing what must be done.”

At first I bristled at the idea of having to use the Borg again, after all I had done to take them off the Treklit board in Star Trek Destiny. But I got over that and came to see it as an opportunity to let Picard face his greatest fear and foe one last time — a fitting last hurrah for his big send-off.

TREKCORE: Despite its scope and size, the Coda trilogy didn’t touch on all of the characters in the literary continuity — was there anyone you wished you could have included that didn’t make the cut?

MACK: I would have liked to have had a bit more time with Ambassador Spock in book three, but for the sake of narrative momentum, I had to cut some bits I had planned for him. Likewise, it would have been nice to have been able to take some asides to revisit Jake Sisko and his family, along with Kasidy and Rebecca, before it all came crashing down.

But the truth is, I just didn’t have the time for such tangential explorations, and the story was already on the verge of becoming unwieldy. As it stands, I like the pacing of Oblivion’s Gate, even though it’s the longest Star Trek novel I’ve ever written (over 140,000 words).

In the best of all worlds, we’d have had unlimited time to polish the story, rewrite, expand ideas, etc. But we were all on various deadlines and dealing with other sources of pressure in our real lives, so we did what we could in the time we had.

If there are other stories that readers wish could have been told before the curtain fell… well, that’s life. And death. Things get left unfinished, words left unsaid, deeds left undone.

TREKCORE: For those that did make it, which of the character moments really pleased you — and which were the hardest to write?

MACK: The one that took me by surprise, popping up its head only after we started hammering out the shape of the story, was the star-crossed romance subplot for Commander Worf and K’Ehleyr of the Mirror Universe.

It takes the characters by surprise, as well, and watching them both get knocked for a loop by it was some of the most fun I had while writing Oblivion’s Gate — even though I knew it all had to lead to one of the book’s most profound moments of tragedy.

But there are so many moments that would qualify as hard to write… how do I choose just one? La Forge saying his final farwell to Data; Beverly Crusher witnessing Wesley’s last sacrifice; the glorious deaths of Worf and his family; Riker feeling the deaths of Deanna and Natasha through the empathic imzadi bond; Picard succumbing to “oblivion’s inevitable embrace.”

Basically, all of Part III: The Measure of a Life.

TREKCORE: The Coda trilogy ends on a definitive, that’s-all-there-is conclusion — was that always the approach, or did you look to leave on a more open-ended note?

MACK: That decision was probably the single greatest point of contention among us, and it was one that took us quite some time to resolve. The notion of the fictional in-universe timeline being disrupted and coming undone obviously grew out of the real-world circumstances that had led to Coda’s development; the new TV series had to take priority over the novel continuity.

Another issue we debated was what would constitute a sufficiently “epic” story to serve as the sign-off for 20 years of work? It couldn’t just be another local threat overcome. I felt we needed something massive, something beyond astronomical — the kind of thing that defies true understanding of its scale. The notion of a “temporal apocalypse” seemed to fit the bill.

Even so, we went back and forth for weeks, maybe even months, over how to resolve the story. Should the characters be able to reverse the threat and save their timeline? Should they save their timeline by somehow severing it from the rest of the multiverse? Or did we want to leave the ending ambiguous, so that readers could decide for themselves whether it ended or continued?

Each approach has its merits and its faults. On the one hand, a “happy ending” might seem like a good way to end things, but how does one make such a conclusion feel earned? And if we posited that the Treklit universe would continue, albeit beyond our further observation, how was that any different from simply abandoning its story arcs? If the conclusion of an epic such as this is merely a salvation of a status quo that we don’t get to see again, then we’ve accomplished exactly nothing. Our heroes have sacrificed nothing, fought and died for nothing.

Similar dramatic weaknesses plagued all versions of the “happy ending,” to one degree or another. Severing the Treklit timeline from the multiverse to save the multiverse seems like a fine notion — except, again, what have we done but preserve a status quo at no real cost? What would be the consequence of severing a timeline from the multiverse? How does that change anything? Does it make the timeline unstable? Subject it to spontaneous unraveling? How do we dramatize that? How does that make for an ending?

Of course, taking the “downer” ending has its own dangers. No doubt it would have some vocal minority of our readers hollering that we just “killed” Treklit for nothing, that it was all just some mindless bloodbath or some such nonsense. Never mind if our characters knowingly make a sacrifice for a greater good they will never enjoy — some folks would see only the loss and not the courage or the selflessness that it represents.

An ambiguous ending felt like a cop-out. A dodge. An attempt to avoid criticism from either side. It’s also not an ending. One of the risks of storytelling is that, sometimes, one must make a choice, a dramatic decision, that will leave some portion of one’s audience unsatisfied.

When we made our decisions about the ending of Oblivion’s Gate — how it would be represented, and what it all would mean — we had a clear dramatic objective in mind. Some readers will appreciate it; some will not.

All I can say to those who don’t like our choice is that we stand by it.

TREKCORE: Now that Coda has finally landed, can we expect more Star Trek writing from David Mack anytime soon?

MACK: Sadly, no. My consultancies on the animated Star Trek series Lower Decks and Prodigy have both concluded, and I am not presently under contract for any new work, at Star Trek or anywhere else. I have some ideas and outlines done for new original novels, but I suspect it will be a very long time before those are ready to go out on submission.

I keep hoping that the phone will ring and I’ll get a call to join a Star Trek series’ writers’ room, or that the editors will ask me to write a novel for Star Trek: Strange New Worlds or a tale of the Fenris Rangers for a Star Trek: Picard novel.

But for now my schedule is alarmingly blank… so if there are any tie-in book editors out there looking for someone to write a novel (*cough* Star Wars), please contact my agent!

David Mack is the award-winning and New York Times bestselling author of thirty-six novels of science fiction, fantasy, and adventure, including the Star Trek: Destiny and Cold Equations trilogies. His writing credits span several media, including television (for episodes of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine), short fiction, and comic books.

He resides in New York City. More information can be found at Mack’s official website.

![]()

The entire Star Trek: Coda trilogy — Dayton Ward’s Star Trek: Coda #1 — Moments Asunder, James Swallow’s Star Trek: Coda #2 — The Ashes of Tomorrow, and David Mack’s Star Trek: Coda #3 — Oblivion’s Gate — are in stores now.